The website of Author/Writer and Psychic Medium Astrid Brown. Making the most of 'YOU' i.e. how to achieve well-being and beauty from within ourselves holistically.

On Amazon

| Astrid Brown (Author) Find all the books, read about the author, and more. See search results for this author |

Google Website Translator Gadget

FB PLUGIN

Traffic: google-analytics.com

Pages

- Home

- BIOGRAPHY

- PSYCHIC DEVELOPMENT

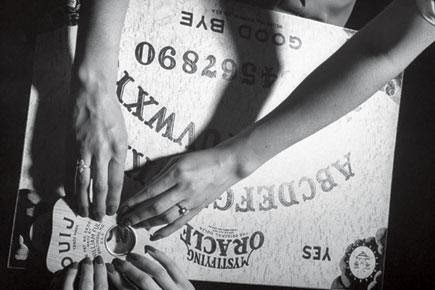

- WORKING WITH SPIRIT

- BOOK OF SHADOWS

- QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS ON ALL ASPECTS OF PSYCHIC MEDIUMSHIP

- TAROT CLASS

- ASTROLOGY

- INNER BEAUTY/PHILOSOPHY

- HOLISTIC THERAPIES/STRESS SOLUTIONS

- STRESS AND HEALTH

- MENTAL HEALTH

- SIMPLE ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY FOR BEGINNERS

- SKIN CARE/GROOMING/COSMETICS

- MY AMAZON AUTHOR PAGE

- FOLLOW ME ON TWITTER

- FACEBOOK PAGE

The website of Author/Writer and Psychic Medium Astrid Brown. Making the most of 'YOU' i.e. how to achieve well-being and beauty from within ourselves. A truly holistic blog providing information on all aspects of psychic mediumship, spiritualism, philosophy, holistic therapies, nutrition, health, stress, mental health and beauty with a little bit of Wicca for good measure. Feeling and looking good is as much a part of how we feel inside as the outside.

Twitter /Pinterest follow

SITE HITS

COPYRIGHT NOTICE

I am a great believer in Karma, but just what is it? Karma comes from the Sanskrit and ancient Indian Language with the underlying principal that every deed in our lives will affect our future life. For example, if we treat others badly during our lifetime we will have negative experiences later on in that lifetime or in future lifetimes. Likewise, if we treat others well we will be rewarded by positive experiences.

Featured post

THE DANGERS OF INEXPERIENCED PSYCHICS/MEDIUMS

Today I am blogging about inexperienced Psychics/Mediums. There are many psychics/mediums around who give the profession a bad name, t...

Search This Blog

Archive of past posts

Saturday, 17 March 2012

SHOULD PARENTS STOP THEIR VERY DISABLED CHILDREN FROM GROWING UP?

FOLLOW ME ON FACEBOOK

PSYCHIC QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

IS IT REALLY POSSIBLE TO FORECAST THE FUTURE AND OTHER QUESTIONS?

Tweet